Katapayadi sutra

Katapayadi sutra is the numerical notation in ancient Indian system to depict letters to numerals for easy remembrance of numbers as meaningful words.

Katapayasi Sankya

Grahacaranibandhana based in the year 683 CE and Laghubhaskariyavivarana based in the year 869 CE speak of a certain numerical notation which goes by the name of Katapayadi Sankhya.

Under this system, a number is ascribed to each and every alphabet of the script, a concept highly similar to the ASCII system in computers.

Grahacaranibandhana based in the year 683 CE and Laghubhaskariyavivarana based in the year 869 CE speak of a certain numerical notation which goes by the name of Katapayadi Sankhya.

Under this system, a number is ascribed to each and every alphabet of the script, a concept highly similar to the ASCII system in computers.

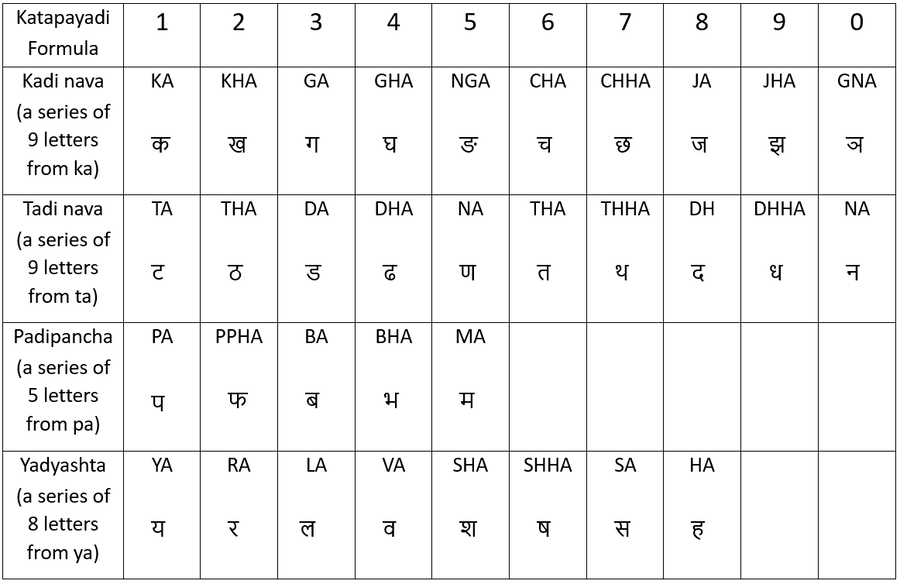

The first two syllables of the name of each melakartha raga have been so ingeniously and dexterously fitted in as to make them subserve the purposes of this formula. This formula is based on the principal letters of the Sanskrit alphabet. The letters of the alphabet are divided off into compartments as shown above and for the purpose of this formula, each letter takes the number under which it falls. In the column next to 9 the figure 0 is placed instead of 10.

Application – Take the first two syllables from the name of given melakartha raga whose serial number in the above table the initial letters of the two syllables fall and write down the two numbers in order. Now reverse this number of two digits and the resulting figure gives the serial number of the given melakartha raga.

Examples:

The name of the given melakartha raga whose serial number is to be determined is Mayamalavagaula. In this raga, the first two syllables are ma and ya; ma or m occurs in column 5 and ya or y in column 1; the resulting figure is 51. Now reverse this number. The result is 15. 15 is the serial number of the Mayamalavagaula melakartha raga.

Navanitam is the name of given melakartha raga. The first two syllables here are na and va and their initial letters n and v, which give the figure 04. By reversing this we get 40. 40 is the serial number of the melakartha raga Navanitham.

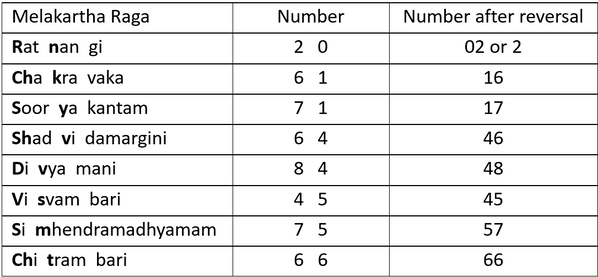

In the case of the following melakartha ragas: Ratnangi, Chakravakam, Sooryakantam, Shadvidamargini, Divyamani, Visvambari, Simhendramadhyamam and Chitrambari, on account of the presence of Samyukta aksharas (conjunct consonants) the first two syllables have to be taken in the following manner, in the order that the application of the Katapayadi formula might hold good.

Application – Take the first two syllables from the name of given melakartha raga whose serial number in the above table the initial letters of the two syllables fall and write down the two numbers in order. Now reverse this number of two digits and the resulting figure gives the serial number of the given melakartha raga.

Examples:

The name of the given melakartha raga whose serial number is to be determined is Mayamalavagaula. In this raga, the first two syllables are ma and ya; ma or m occurs in column 5 and ya or y in column 1; the resulting figure is 51. Now reverse this number. The result is 15. 15 is the serial number of the Mayamalavagaula melakartha raga.

Navanitam is the name of given melakartha raga. The first two syllables here are na and va and their initial letters n and v, which give the figure 04. By reversing this we get 40. 40 is the serial number of the melakartha raga Navanitham.

In the case of the following melakartha ragas: Ratnangi, Chakravakam, Sooryakantam, Shadvidamargini, Divyamani, Visvambari, Simhendramadhyamam and Chitrambari, on account of the presence of Samyukta aksharas (conjunct consonants) the first two syllables have to be taken in the following manner, in the order that the application of the Katapayadi formula might hold good.

The Katapayadi formula does not apply to the names of the names of the janya ragas.

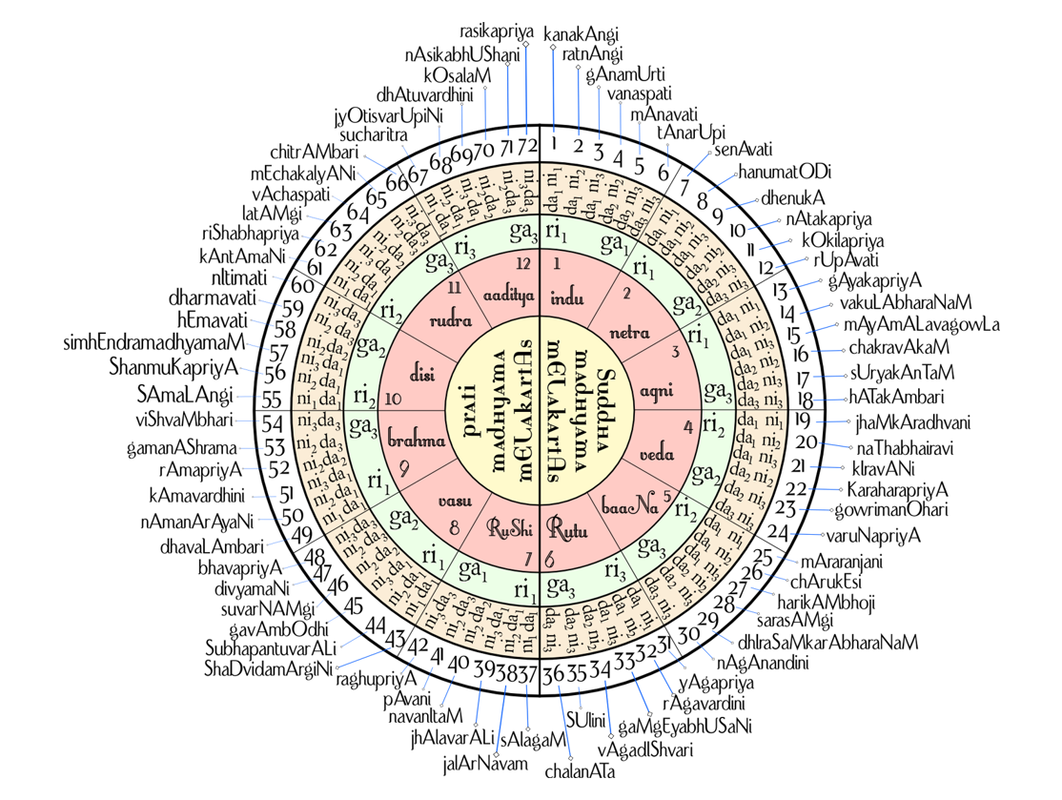

In the formation of the melakartha ragas, all possible combinations of notes (tones ad semitones) which a refined ear can tolerate and easily distinguish have been included. The melakartha scheme is the rocky foundation upon which South Indian Musi firmly rests to-day. Viewed in the light of mere permutations and combinations, the scheme might appear at first sight as an artificial and dry arithmetical process. But ‘the Charm and Beauty of music lie deep in the Theory of Numbers’ and every musical sound and interval has its exact number of vibrations and ratios. The melakartha scheme is highly comprehensive and systematic and includes within its fold all the modes used in ancient as well as modern systems of music of the different parts of the world. It is a complete and exhaustive scheme evolved by the simple and natural combinations already explained.

In the formation of the melakartha ragas, all possible combinations of notes (tones ad semitones) which a refined ear can tolerate and easily distinguish have been included. The melakartha scheme is the rocky foundation upon which South Indian Musi firmly rests to-day. Viewed in the light of mere permutations and combinations, the scheme might appear at first sight as an artificial and dry arithmetical process. But ‘the Charm and Beauty of music lie deep in the Theory of Numbers’ and every musical sound and interval has its exact number of vibrations and ratios. The melakartha scheme is highly comprehensive and systematic and includes within its fold all the modes used in ancient as well as modern systems of music of the different parts of the world. It is a complete and exhaustive scheme evolved by the simple and natural combinations already explained.

According to the Kadapayadi formula, the syllables pa, sri, go, bhu, ma and sha mnemonically represent the 1st, 2nd , 3rd , 4th , 5th, and 6th melas of each chakra. These syllables by themselves indicate the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. When these syllables are fixed on to the chakra names, we can calculate the serial number of the mela. Each chakra contains 6 melas.

Example:

Indu-pa - 1st mela

Agni-go - 15th mela (Agni is the 3rd chakra, {2 x 6} + 3 giving 15)

Bhutha Sankya

The names of the chakras are based on Bhutha Sankya which are related to our planet and are themselves suggestive of their numbers. The 12 chakras are:

Indu stands for the moon, of which we have only one – hence it is the first chakra.

Netra means eyes, of which we have two – hence it is the second.

Agni is the third chakra as it denotes the three divyagnis (fire, lightning and Sun).

Veda denoting four Vedas is the name of the fourth chakra.

Bana comes fifth as it stands for the five bāṇaa of Manmatha. (pancha banaas)

Ritu is the sixth chakra standing for the 6 seasons of Hindu calendar. (shat ritus)

Rishi, meaning sage, is the seventh chakra representing the seven sages. (sapta rishis)

Vasu stands for the eight vasus of Hinduism. (shta vasus)

Brahma comes next of which there are 9. (nava brahmas)

Disi - the 10 directions are represented by the tenth chakra.

Rudra is the eleventh chakra of which there are eleven. (ekadasa rudras)

Aditya is the twelfth chakra of which there are twelve suns. (dvadasa adithyas)

|

Gmail : vaikampadmakrishnan@gmail.com

Mobile & WhatsApp : +91 9446535161 Skype : vaikampadmakrishnan Instagram : Vaikam Padma Krishnan |