Raga

A raga uses a series of five or more musical notes upon which a melody is constructed. The way the notes are approached and rendered in musical phrases and the mood they convey are more important in defining a raga.

In Carnatic music, rāgas are classified as Janaka rāgas and Janya rāgas. Janaka rāgas are the rāgas from which the Janya rāgas are created. Janaka rāgas are grouped together using a scheme called Katapayadi sutra and are organised as Melakarta rāgas.

A raga uses a series of five or more musical notes upon which a melody is constructed. The way the notes are approached and rendered in musical phrases and the mood they convey are more important in defining a raga.

In Carnatic music, rāgas are classified as Janaka rāgas and Janya rāgas. Janaka rāgas are the rāgas from which the Janya rāgas are created. Janaka rāgas are grouped together using a scheme called Katapayadi sutra and are organised as Melakarta rāgas.

The outstanding feature of Indian music is the raga system. Every raga is a distinct musical entity by itself and processes well defined characteristics. The ideal of absolute music is reached in the concept of raga. Ragas are so many statues visible , or rather perceivable , by the aural sense. They are a solid musical fact and every musician is cognisant of them. Each raga has a separate aesthetic form and can be recognised by a trained ear.

Musical compositions are concrete forms of abstract raga. They are so many manifestations of the various facts of the raga. They are the mirrors or channels through which we can see the forms of the raga. The beauties underlying a raga are subtle and delicate. Whereas musical composition presents only a certain aspect of a raga , the detailed alapana of the same raga enables us to see its full form. Theoretically , the number of ragas is infinite. Singing or performing raga alapana (raga exposition) demands the highest degree of musical training , culture and creativeness. Some ragas admit of an elaborate exposition. Such ragas are called Major ragas. Ragas which admit of only a brief exposition are called Minor ragas.

Musical compositions are concrete forms of abstract raga. They are so many manifestations of the various facts of the raga. They are the mirrors or channels through which we can see the forms of the raga. The beauties underlying a raga are subtle and delicate. Whereas musical composition presents only a certain aspect of a raga , the detailed alapana of the same raga enables us to see its full form. Theoretically , the number of ragas is infinite. Singing or performing raga alapana (raga exposition) demands the highest degree of musical training , culture and creativeness. Some ragas admit of an elaborate exposition. Such ragas are called Major ragas. Ragas which admit of only a brief exposition are called Minor ragas.

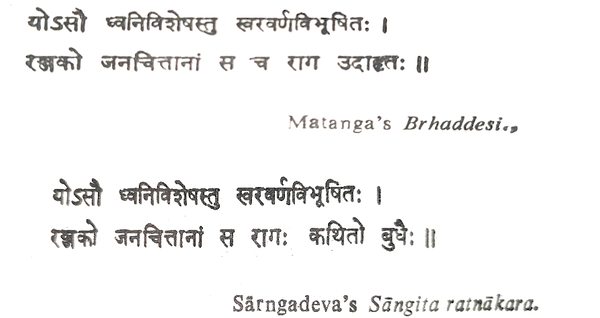

According to the above slokas, a raga is that which is beautified or decorated by the tonal excellence of swaras and varnas and which decorations gives pleasure to the mind of the listener. It is the sequence or combinations of appropriate __ varnas that goes to make or establish a raga . Varna here means the mode of singing – gana kriya.

Swaras in a raga are arranged in ascending and descending order. Ascending order is called Arohana, and the descending order is called Avarohana.

Swaras in a raga are arranged in ascending and descending order. Ascending order is called Arohana, and the descending order is called Avarohana.

Classification

The subject of raga classification in Indian music maybe studied under the following heads:

1.Raga classification in ancient music including the classification that prevailed in ancient Tamil music .

2.Raga classification in Hindustani music .

3.Raga classification in Carnatic music.

Of these, the third classification will be discussed below.

The modern conception of a raga dates from the time of Matanga Muni ( 5th century A.D. ). The classification of ragas into Janaka ragas and Janya ragas is the most scientific system of raga classification.

The terms Janaka raga, Melakarta raga, Mela raga, Karta raga, Sampurna raga, Parent raga, Fundamental raga, Root raga and Primary raga are all synonymous and mean the same thing. Likewise, Janya ragas are known by other names as Derivative ragas and Secondary ragas. Janaka means generic and Janya means generated.

Janya raga is a raga, which is said to be born or derived from a Melakarta raga. There are 72 Melakarta Ragas. Every Janya raga has its parent scale or janaka raga. Hence the names Derivative raga and Secondary raga. It takes the same svaras as the svaras taken by its parent raga. Example: Mayamalavagaula is the Janaka raga of Malahari. There are 72 Janaka ragas based on the twelve swarasthanas of the sthayi . The scheme of 72 melakarta ragas provides an excellent , workable arrangement. Whereas the number of janaka ragas is fixed , the number of janya ragas is practically unlimited .

The subject of raga classification in Indian music maybe studied under the following heads:

1.Raga classification in ancient music including the classification that prevailed in ancient Tamil music .

2.Raga classification in Hindustani music .

3.Raga classification in Carnatic music.

Of these, the third classification will be discussed below.

The modern conception of a raga dates from the time of Matanga Muni ( 5th century A.D. ). The classification of ragas into Janaka ragas and Janya ragas is the most scientific system of raga classification.

The terms Janaka raga, Melakarta raga, Mela raga, Karta raga, Sampurna raga, Parent raga, Fundamental raga, Root raga and Primary raga are all synonymous and mean the same thing. Likewise, Janya ragas are known by other names as Derivative ragas and Secondary ragas. Janaka means generic and Janya means generated.

Janya raga is a raga, which is said to be born or derived from a Melakarta raga. There are 72 Melakarta Ragas. Every Janya raga has its parent scale or janaka raga. Hence the names Derivative raga and Secondary raga. It takes the same svaras as the svaras taken by its parent raga. Example: Mayamalavagaula is the Janaka raga of Malahari. There are 72 Janaka ragas based on the twelve swarasthanas of the sthayi . The scheme of 72 melakarta ragas provides an excellent , workable arrangement. Whereas the number of janaka ragas is fixed , the number of janya ragas is practically unlimited .

The janaka-janya system of raga classification need not give rise to the presumption that all janaka ragas are older than janya ragas. In fact, a good number of these janaka ragas came into existence only during the modern period of Indian music. Many janya ragas like Bhupala , Ahiri , Nadanamakriya , Gaula , Vasanta , Saurashtra , Madhyamavati , Kedaragaula , Mohana , Kambhoji and Nilambari have been in existence for more than a thousand years. The raga , Kathanakutuhalam may be mentioned as an example of a janya raga , which came into existence after the scheme of 72 Malakartas was conceived of.

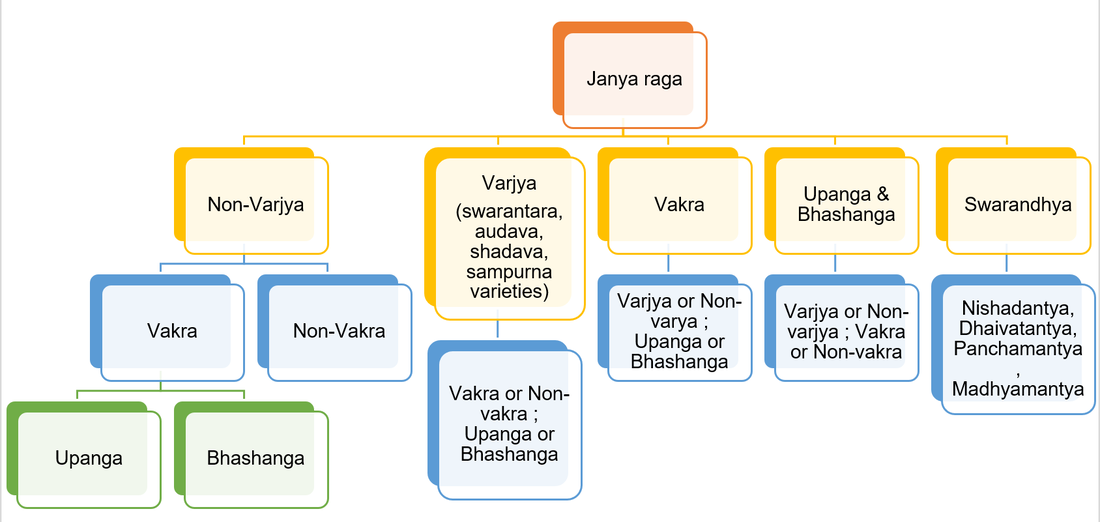

Janya ragas are classified into:

Janya ragas need not be Sampoorna either in the arohana or avarohana or both taken together. One or two or sometimes even three swaras may be absent or deleted. This aspect is technically known as varjya.

Varjya ragas are of three varieties: arohana varjya, avarohana varjya and ubhaya varjya – with both arohana and avarohana varjya. Besides these three, there are also krama varjya and vakra varjya ragas.

Arohana varjya ragas : Saveri, Arabhi, Bilahari, Dhanyasi, Salagabhairavi

Avarohana varjya ragas: Saramati, Kaikavasi, Dundubhi, Chaturangini, Garudadhwani

Ubhaya varjya ragas: Mohanam, Hamsadhwani, Suddha Saveri, Madhyamavati Nagaswaravali

Janya ragas are classified into:

- Varja Ragas

- Vakra Ragas

- Upanga Ragas

- Bhashanga Ragas

- Nishadantya Ragas, Daivatantya Ragas, Panchamantya Ragas & Madhyamantya Ragas

Janya ragas need not be Sampoorna either in the arohana or avarohana or both taken together. One or two or sometimes even three swaras may be absent or deleted. This aspect is technically known as varjya.

Varjya ragas are of three varieties: arohana varjya, avarohana varjya and ubhaya varjya – with both arohana and avarohana varjya. Besides these three, there are also krama varjya and vakra varjya ragas.

Arohana varjya ragas : Saveri, Arabhi, Bilahari, Dhanyasi, Salagabhairavi

Avarohana varjya ragas: Saramati, Kaikavasi, Dundubhi, Chaturangini, Garudadhwani

Ubhaya varjya ragas: Mohanam, Hamsadhwani, Suddha Saveri, Madhyamavati Nagaswaravali

Krama varjya ragas can be sampoorna, shadava, audava, or swarantara. In ancient Tamil music, shadava was known as 'Panniam' , audava was called 'Tiram' and svarantara was known as 'Tiratiram'.

The arohana and avarohana should individually be described if the number of swaras present is different in each one of them.

An audava raga with both ma and pa deleted will lack stability and will be somewhat nebulous in character. Madhyama and Panchama being the samvadi swaras ( consonantal notes) of shadja , it is necessary that at least one of them should be present in a raga , swaras which are eschewed in a raga , if introduced , will shatter its melodic individuality . Such notes will sound as apasvaras ( wrong notes ) for the raga and will produce a repulsive effect .

Vakra ragas are classified according as the arohana or avarohana or both are vakra :

Since the arohana or avarohana in these three cases may be audava , shadava or sampurna , a further classification of vakra ragas is as follows :

Krama sampurna – Vakra sampurna ( Karnatakabyag )

Vakra sampurna – Krama sampurna ( Kathanakutuhalam)

Krama sampurana – Vakra shadava ( Umabharanam )

Vakra shadava – Krama sampurana ( Mukhari )

Krama sampurna – Vakra audava

Vakra audava – Krama sampurna ( Nabhomani )

Vakra sampurna – Vakra sampurna ( Sahana )

Vakra shadava – Vakra sampurna ( Narayanagaula )

Vakra audava – Vakra sampurna ( Dipaka )

- In a sampoorna raga all the seven notes are present in both arohana and avarohana.

- If only six swaras are present either in the arohana or avarohana, it is described as a shadava raga.

- A raga with only five swaras in the ascent and descent is described as an audava raga.

- A raga with four notes is known as swarantara.

The arohana and avarohana should individually be described if the number of swaras present is different in each one of them.

- Audava Audava raga: Both Arohana and Avarohana contain only 5 notes. Eg: Mohana

- Audava Shadava raga: Arohana contains 5 notes, Avarohana contains 6 notes.

- Audava Sampoorna raga: Arohana contains 5 notes, Avarohana contains all 7 notes.

- Shadava Shadava raga: Both Arohana and Avarohana contain only 6 notes.

- Shadava Audava raga: Arohana contains 6 notes, Avarohana contains 5 notes.

- Shadava Sampoorna raga: Arohana contains 6 notes, Avarohana contains all 7 notes.

- Sampoorna Shadava raga: Arohanam contains all 7 notes , Avarohanam contains 6 notes.

- Sampoorna Audava: Arohanam contains all 7 notes , Avarohanam contains 5 notes.

An audava raga with both ma and pa deleted will lack stability and will be somewhat nebulous in character. Madhyama and Panchama being the samvadi swaras ( consonantal notes) of shadja , it is necessary that at least one of them should be present in a raga , swaras which are eschewed in a raga , if introduced , will shatter its melodic individuality . Such notes will sound as apasvaras ( wrong notes ) for the raga and will produce a repulsive effect .

Vakra ragas are classified according as the arohana or avarohana or both are vakra :

- Krama arohana – Vakra avarohana

- Vakra arohana – Krama avarohana

- Upaya vakra ( both arohana and avarohana are vakra )

Since the arohana or avarohana in these three cases may be audava , shadava or sampurna , a further classification of vakra ragas is as follows :

Krama sampurna – Vakra sampurna ( Karnatakabyag )

- Krama shadava – Vakra sampurna ( Darbar )

Vakra sampurna – Krama sampurna ( Kathanakutuhalam)

- Vakra sampurna – Krama shadava (Ardradesi)

Krama sampurana – Vakra shadava ( Umabharanam )

- Krama shadava – Vakra shadava ( Devamanohari )

Vakra shadava – Krama sampurana ( Mukhari )

- Vakra shadava – Krama shadava ( Vijayasri )

Krama sampurna – Vakra audava

- Krama shadava – Vakra audava

Vakra audava – Krama sampurna ( Nabhomani )

- Vakra audava – Krama shadava ( Kedaram )

Vakra sampurna – Vakra sampurna ( Sahana )

- Vakra sampurna – Vakra shadava ( Nilambari )

Vakra shadava – Vakra sampurna ( Narayanagaula )

- Vakra shadava – Vakra shadav ( Bindu malini )

Vakra audava – Vakra sampurna ( Dipaka )

- Vakra audava – Vakra shadava ( Bangala )

Upanga ragas are those janya ragas, which take only notes, present in their respective parent ragas. Malahari, Sudda saveri, Arabhi and Mohana are examples.Malahari takes notes from its parent raga Mayamalavagoula ragam.

Upanga ragas can be classified into:

Bhashanga ragas are those janya ragas which in addition to the notes pertaining to their parent ragas, take one or two foreign notes as visitors. These visiting notes come only in a particular sancharas and serve to increase the beauty of raga.

The swarupa of the raga is revealed better by these foreign notes. Thus in a bhashanga raga, both the varities of a swara occur, the variety pertaining to the melakarta being called the swakiya swara and visiting note, the anya swara. The number of Bhashanga ragas used in Carnatic music is 26.

In Bilahari and Bhairavi, the kaisiki nishada and Chatussruti Dhaivata are the respective anya svaras; the swakiya svaras for the two ragas being kaakali nishada and suddha dhaivata respectively.

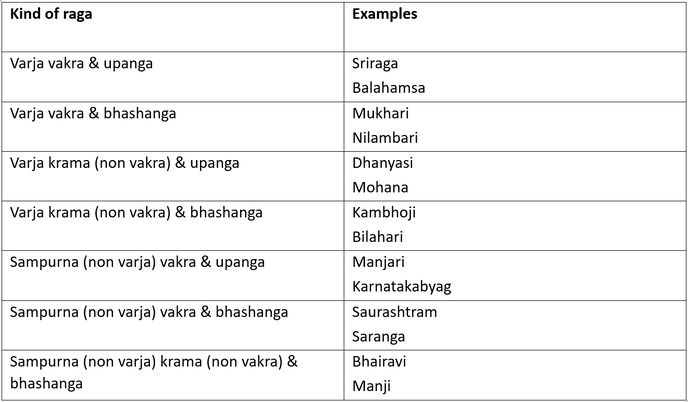

These classifications are however not mutually exclusive . For eg. , a varja raga can be vakra and upanga ; and a varja raga can be vakra and bhashanga. Likewise a varja raga can be non-vakra and upanga or bashanga. Again there are non-varja , vakra ragas of both the upanga and bhashanga types and non-varja , non-vakra ragas of the bhashanga types.

In a vakra raga , the note at which the obliquity takes place is called the vakra swara , the note at which the obliquity terminates the original course is resumed is called the vakrantya swara. The length of obliquity is the compass of vakratva.

Upanga ragas can be classified into:

- Upanga Krama ragas Eg: Mohana ragam

- Upanga Vakra ragas Eg: Sahana ragam

- Upanga Varja ragas Eg: Mohana ragam

- Upanga Sampurna ragas Eg: Sahana ragam

Bhashanga ragas are those janya ragas which in addition to the notes pertaining to their parent ragas, take one or two foreign notes as visitors. These visiting notes come only in a particular sancharas and serve to increase the beauty of raga.

The swarupa of the raga is revealed better by these foreign notes. Thus in a bhashanga raga, both the varities of a swara occur, the variety pertaining to the melakarta being called the swakiya swara and visiting note, the anya swara. The number of Bhashanga ragas used in Carnatic music is 26.

In Bilahari and Bhairavi, the kaisiki nishada and Chatussruti Dhaivata are the respective anya svaras; the swakiya svaras for the two ragas being kaakali nishada and suddha dhaivata respectively.

These classifications are however not mutually exclusive . For eg. , a varja raga can be vakra and upanga ; and a varja raga can be vakra and bhashanga. Likewise a varja raga can be non-vakra and upanga or bashanga. Again there are non-varja , vakra ragas of both the upanga and bhashanga types and non-varja , non-vakra ragas of the bhashanga types.

In a vakra raga , the note at which the obliquity takes place is called the vakra swara , the note at which the obliquity terminates the original course is resumed is called the vakrantya swara. The length of obliquity is the compass of vakratva.

Classifications of Bhashanga Ragas:

Bhashanga ragas like Kambhoji , Bilahari , Nilambari and Saranga take only one foreign note. Those like Hindusthan Behag take ywo foreign notes. There are a few bhashanga ragas like Hindusthan Kafi which takes three foreign notes.

I.From the point of view of the number of anya swaras ( foreign notes ) taken , bhashanga ragas may be classified into:

1.Ekanyaswara bhashanga raga : taking only one foreign note. ( Mukhari )

2.Dvi-anyaswara bhashanga raga : taking two foreign notes. ( Athana )

3.Tri-anyaswara bhashanga raga : taking three foreign notes. ( Hindusthan Kafi )

In 2 and 3 , the anya swaras may be taken as pertaining to one or two different melas. Three is the maximum number of anya swaras that can come in a bhashanga raga.

II.Bhashanga ragas wherein the anya swara occurs as a kampita swara ; example sadharana Gandhara in Athana & abhashanga ragas wherein the anya swara comes as plain or ungraced note ; example Kakali nishadam in Kambhoji.

III.In Bhashanga ragas , the accidentals usually figure in sancharas. But in a few cases, the accidental note is incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga itself. That s to say, anya swara is heard even when merely the scale or the murchana is sung. Asaveri , Bhairavi , Anandabhairavi , Mukhari , Chintamani and Saranga are good examples of this type of bhashanga ragas.

1.Where the anya swara is incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga. This admits to two further divisions :

(a)Wherein the foreign note is incorporated in the arohana ; ex. Bhairavi and Mukhari

(b)Wherein the foreign note is incorporated in the avarohana ; ex. Asavari and Saranga

2.Where the anya swara is not incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga , but occurs only in the sancharas of the raga. In this type of bhashanga raga , it is possible to establish the melodic individuality of the raga, without touching phrases containing the foreign note ( Bilahari raga is an instance in point ).

Whereas the compulsory use of the anya swara is the feature of the former type of bhashanga raga , the optional use of anya swara is feature of the latter type.

Bhashanga ragas like Kambhoji , Bilahari , Nilambari and Saranga take only one foreign note. Those like Hindusthan Behag take ywo foreign notes. There are a few bhashanga ragas like Hindusthan Kafi which takes three foreign notes.

I.From the point of view of the number of anya swaras ( foreign notes ) taken , bhashanga ragas may be classified into:

1.Ekanyaswara bhashanga raga : taking only one foreign note. ( Mukhari )

2.Dvi-anyaswara bhashanga raga : taking two foreign notes. ( Athana )

3.Tri-anyaswara bhashanga raga : taking three foreign notes. ( Hindusthan Kafi )

In 2 and 3 , the anya swaras may be taken as pertaining to one or two different melas. Three is the maximum number of anya swaras that can come in a bhashanga raga.

II.Bhashanga ragas wherein the anya swara occurs as a kampita swara ; example sadharana Gandhara in Athana & abhashanga ragas wherein the anya swara comes as plain or ungraced note ; example Kakali nishadam in Kambhoji.

III.In Bhashanga ragas , the accidentals usually figure in sancharas. But in a few cases, the accidental note is incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga itself. That s to say, anya swara is heard even when merely the scale or the murchana is sung. Asaveri , Bhairavi , Anandabhairavi , Mukhari , Chintamani and Saranga are good examples of this type of bhashanga ragas.

1.Where the anya swara is incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga. This admits to two further divisions :

(a)Wherein the foreign note is incorporated in the arohana ; ex. Bhairavi and Mukhari

(b)Wherein the foreign note is incorporated in the avarohana ; ex. Asavari and Saranga

2.Where the anya swara is not incorporated in the arohana and avarohana of the raga , but occurs only in the sancharas of the raga. In this type of bhashanga raga , it is possible to establish the melodic individuality of the raga, without touching phrases containing the foreign note ( Bilahari raga is an instance in point ).

Whereas the compulsory use of the anya swara is the feature of the former type of bhashanga raga , the optional use of anya swara is feature of the latter type.

IV.Bhashanga raga known as such from their inception; ex. Bhairavi ; and bhashanga ragas which were formally upanga and became bhashanga later on ; ex. Khamas.

While some bhashanga ragas like Bhairavi ( Pan Kausikam of Tevaram ) had a natural origin , many of the other bhashanga ragas were originally of the upanga type. People gradually discovered the enhanced beauty of the ragas when foreign notes were introduced and sung. The vidvans as well as the listeners relished the changes and slowly acquiesced in them. Khambhoji which was an upanga raga centuries ago , became a bhashanga raga only later on. In the Tevaram , one can hear hymns which represent the upanga and the bhashanga types of Khambhoji . Khamas is an example of a janya raga which became bhashanga in the latter part of the 19th century. Let it be remembered that Tyagaraja’s Khamas as seen in his two kritis : Sujanajivana and Sitapate is only an upanga raga. Therefore in bhashanga raga , the raga which would have been the janaka raga , in it prior upanga condition is presumed to be the parent mela even after the change.

In the bhashanga raga , there need not necessarily be the trace of a foreign raga. The accidental not is only a welcome visitor and swaras to establish the Swarupa of the raga. The foreign note as a rule should not unduly emphasised in bhashanga raga.

V.In Bhashanga ragas the foreign note will be found to be a samvadi swara of some other note occurring in the raga. Thus in Bhairavi , the forign note is a samvadi swara of chaturdruti rishabha ; likewise in Khambhoji raga the Kakali nishada is a consonantal note of antara gandhara.

VI.Purna bhashanga and Ardha bhashanga ragas. The test for a bhashanga raga , is that the foreign note should belong to a swarasthana not pertaining to its parent scale. The occurrence or the slight sharpening or flattening of the self-same not will not suffice.

For example, ragas like Saveri and Begada present an interesting study in this connection. In some specific sancharas therein, some notes are sung slightly flattened or sharped but not to such an extent as to be considered as belonging to the neighbouring swarasthanas. For example in Saveri , in the pryogas s r g r s and p d n d p , the notes ; ga and ni are slightly flattened and sung ; but they are not so diminished in pitch as to suggest sadarana gandharam and kaishiki nishadam. Again in Begada , in the prayoga p, d n d p the Kakali nishadam is slightly flattened and sung ; but it does not become actually kaishiki nishadam. Such ragas might be called Ardha bhashanga ragas( semi bhashanga ).( Ragas like Kambhoji and Bilahari may be styled as Purna bhashanga ragas). In the Sangitha sampradaya pradarsini , even these ragas , where only a neighbouring sruti is touched are styled bhashanga ragas. In practice it will be found that in many ragas , the frequency of a particular note becomes sharpened by a sruti during the upward trend and gets diminished by a sruti during the downward trend. If the view promulgated by Subbarama Dikshitar is to be accepted , many of our janya ragas have to be dubbed bhashanga ragas.

While some bhashanga ragas like Bhairavi ( Pan Kausikam of Tevaram ) had a natural origin , many of the other bhashanga ragas were originally of the upanga type. People gradually discovered the enhanced beauty of the ragas when foreign notes were introduced and sung. The vidvans as well as the listeners relished the changes and slowly acquiesced in them. Khambhoji which was an upanga raga centuries ago , became a bhashanga raga only later on. In the Tevaram , one can hear hymns which represent the upanga and the bhashanga types of Khambhoji . Khamas is an example of a janya raga which became bhashanga in the latter part of the 19th century. Let it be remembered that Tyagaraja’s Khamas as seen in his two kritis : Sujanajivana and Sitapate is only an upanga raga. Therefore in bhashanga raga , the raga which would have been the janaka raga , in it prior upanga condition is presumed to be the parent mela even after the change.

In the bhashanga raga , there need not necessarily be the trace of a foreign raga. The accidental not is only a welcome visitor and swaras to establish the Swarupa of the raga. The foreign note as a rule should not unduly emphasised in bhashanga raga.

V.In Bhashanga ragas the foreign note will be found to be a samvadi swara of some other note occurring in the raga. Thus in Bhairavi , the forign note is a samvadi swara of chaturdruti rishabha ; likewise in Khambhoji raga the Kakali nishada is a consonantal note of antara gandhara.

VI.Purna bhashanga and Ardha bhashanga ragas. The test for a bhashanga raga , is that the foreign note should belong to a swarasthana not pertaining to its parent scale. The occurrence or the slight sharpening or flattening of the self-same not will not suffice.

For example, ragas like Saveri and Begada present an interesting study in this connection. In some specific sancharas therein, some notes are sung slightly flattened or sharped but not to such an extent as to be considered as belonging to the neighbouring swarasthanas. For example in Saveri , in the pryogas s r g r s and p d n d p , the notes ; ga and ni are slightly flattened and sung ; but they are not so diminished in pitch as to suggest sadarana gandharam and kaishiki nishadam. Again in Begada , in the prayoga p, d n d p the Kakali nishadam is slightly flattened and sung ; but it does not become actually kaishiki nishadam. Such ragas might be called Ardha bhashanga ragas( semi bhashanga ).( Ragas like Kambhoji and Bilahari may be styled as Purna bhashanga ragas). In the Sangitha sampradaya pradarsini , even these ragas , where only a neighbouring sruti is touched are styled bhashanga ragas. In practice it will be found that in many ragas , the frequency of a particular note becomes sharpened by a sruti during the upward trend and gets diminished by a sruti during the downward trend. If the view promulgated by Subbarama Dikshitar is to be accepted , many of our janya ragas have to be dubbed bhashanga ragas.

VII.In Bhadhanga ragas , with a few exceptions , the accidental note comes a lesser number of times compared to the swakiya swara. For example , in any piece in Khambhoji raga , it will be found that Kakali nishada ( foreign note ) occurs a lesser number of times compared to the Kaishiki nishada. So we say that Harikambhoji is the parent raga of Khambhoji on the presumption that Kaishiki nishada is the inherent note or the swakiya swara. Likewise in Bilahari , the Kaishiki nishada occurs a lesser number of times compared to Kakali nishada , and so Bilahari is deemed to be a derivative of Dheera Shankarabharanam and so on.

In the case of some bhashanga ragas , we are in a position to determine their original upanga condition almost accurately. The accidentals were later additions. In a few bhashanga ragas even though the accidentals occur a great number of times compared to swakiya swaras , still they are regarded as Anya swaras only. Anandhabhairavi is a good instance. In this raga , the accidental ( Chatursruti dhaivata ) occurs more frequently than the Suddha dhaivata ; still the raga is presumed to be a derivative of Nattabhairavi only.

VIII.Usually in Bhashanga ragas , the swakiya swara and the anya swara can be sounded in all the three octaves. But Punnagavarali furnishes a remarkable example of a bhashanga raga wherin the swakiya swara ( Kaishiki nishada ) occurs in the madhya stayi and the anya swara ( Kakali nishada ) in the mandra stayi. Punnagavarali raga had its origin in folk music. It is an interesting example of a raga which originated straightway as a bhashanga raga.

The present meaning associated with the term Bhashanga raga is not more than three centuries old. In earlier times , the term connoted quite a different concept. It was regarded by some as a raga of provincial origin. Thus , Saurashtra , Malavi and Surati were called bhashanga ragas. In the same manner , the present meaning associated with the terms , raganga raga and upanga raga are a later development. They had different meanings in earlier times.

Bhashanga ragas are a natural growth. In some works they are referred to as Desanga ragas.

In the case of some bhashanga ragas , we are in a position to determine their original upanga condition almost accurately. The accidentals were later additions. In a few bhashanga ragas even though the accidentals occur a great number of times compared to swakiya swaras , still they are regarded as Anya swaras only. Anandhabhairavi is a good instance. In this raga , the accidental ( Chatursruti dhaivata ) occurs more frequently than the Suddha dhaivata ; still the raga is presumed to be a derivative of Nattabhairavi only.

VIII.Usually in Bhashanga ragas , the swakiya swara and the anya swara can be sounded in all the three octaves. But Punnagavarali furnishes a remarkable example of a bhashanga raga wherin the swakiya swara ( Kaishiki nishada ) occurs in the madhya stayi and the anya swara ( Kakali nishada ) in the mandra stayi. Punnagavarali raga had its origin in folk music. It is an interesting example of a raga which originated straightway as a bhashanga raga.

The present meaning associated with the term Bhashanga raga is not more than three centuries old. In earlier times , the term connoted quite a different concept. It was regarded by some as a raga of provincial origin. Thus , Saurashtra , Malavi and Surati were called bhashanga ragas. In the same manner , the present meaning associated with the terms , raganga raga and upanga raga are a later development. They had different meanings in earlier times.

Bhashanga ragas are a natural growth. In some works they are referred to as Desanga ragas.

Nishadantya, Dhaivatantya, Panchamantya and Madhayamantya Ragas

In some of the janya ragas, the compass of development is restricted to a limited part of the Mandra stayi and Madhya stayi. The Tara stayi shadjam is not touched at all. Such ragas are classified into:

Punnagavarali and Chittaranjini are also Nishadantya ragas. The Sama gana scale ( mgrsndp ) of anicient music stands as an example of a madhyamantya raga.

Janya sampurnas are yet another group of janya ragas. In such ragas, as the name itself indicates, all the sapta swaras are represented in both the arohana and avarohana. Such ragas differ from their respective janaka ragas either by being vakra or bhashanga, or by having special characteristic prayogas which bring out the Swarupa of the raga; or by the compass of its prastara being limited to a defined range. For instance, there is no sanchara for punnagavarali above the tara sthayi Gandhara in the classical compositions. Janya sampurnas; if they are upanga, must necessarily be vakra; if bhashanga, they may be vakra or non-vakra.

In some of the janya ragas, the compass of development is restricted to a limited part of the Mandra stayi and Madhya stayi. The Tara stayi shadjam is not touched at all. Such ragas are classified into:

- Nishadantya : The scale of this raga ends with Madhya sthayi nishada in ascending and mandra sthayi nishada in descending.

- Dhaivatantya : The scale of this raga ends with madhya sthayi dhaivata in ascending and mandra sthayi dhaivata in descending.

- Panchamantya : The scale of this raga ends with madhya sthayi panchama in ascending and mandra sthayi panchama in descending.

- Madhyamantya : the scale of this raga ends with Madhya sthayi Sudha Madhyama in acending and mandrastayi Sudha Madhyama in decending.

Punnagavarali and Chittaranjini are also Nishadantya ragas. The Sama gana scale ( mgrsndp ) of anicient music stands as an example of a madhyamantya raga.

Janya sampurnas are yet another group of janya ragas. In such ragas, as the name itself indicates, all the sapta swaras are represented in both the arohana and avarohana. Such ragas differ from their respective janaka ragas either by being vakra or bhashanga, or by having special characteristic prayogas which bring out the Swarupa of the raga; or by the compass of its prastara being limited to a defined range. For instance, there is no sanchara for punnagavarali above the tara sthayi Gandhara in the classical compositions. Janya sampurnas; if they are upanga, must necessarily be vakra; if bhashanga, they may be vakra or non-vakra.

Fixing Janaka ragas for Janya ragas

It will be useful at this stage to ponder awhile about the rules observed in fixing Janaka raga for Janya ragas. All janya ragas must either be upanga or bhashanga.

The following considerations are taken into account in fixing their janaka ragas :

In the case of the upanga ragas of the audava - sampurna , sampurna- audava , shadava – sampurna and sampurna – vakra varieties , the janaka ragas are easily determined , since all the saptaswaras are represented in either the arohana or avarohana. It is also easy to determine the janaka ragas for the upanga ragas of the shadava – shadava , shadava – audava , audava – shadava and audava – audava types , if in each case , the saptaswaras are found represented in the arohana and avarohana taken together. It is likewise easy to fix the janaka ragas for the Panchama – varjya shadava – shadava , shadava – audava , audava – shadava and audava – audava , ragas of the upanga type , provided the notes rishabha , gandhara , madhyama , dhaivata and nishada are represented in the arohana nad avarohana taken together. The difficulty arise only in the case of those upanga ragas wherein one or two notes are completely eliminated in both the arohana and avarohana.

Taking Mohana , for instance , it might be argued that it can be taken as a derivative of the Dheera Shankarabharana , Vachaspathi and Mecha Kalyani melas also , taking into consideration its swarasthanas. Likewise Sarasangi , Lathangi and Mecha Kalyani might be cited as the other possible janaka melas for Hamsadhwani ; and Nattabhairavi , Charukeshi and Harikambhoji as the other possible janaka melas for Madhyamavathi.

The author of the Sangeetha Kaumudi tried to find a solution for this anormaly by enunciating a new rule – that , all such cases the raga should be allocated to the earliest possible mela in the scheme of 72. This theory naturally ignored all the relevant and important considerations that have weighed with music scholars in the past in fixing the janaka melas for janya ragas considerations like :

were deemed really important in determining the janaka melas. The theory referred to the above takes into consideration only the swarasthanas of a raga. The author of this theory was naturally led to place Kuntalavarali under Vanaspathi , Malahari undr Gayakapriya , Nagaswaravali undr Chakravakam , Madhyamavati under Nattabhairivi and so on.

As a corollary to the theory suggested by the author of the Sangita Kaumudi , we may enunciate the theory that all janya ragas should be allocates to the latest possible melas in the scheme of 72. Mohana and Hamsadwani under this theory will rank as janyas of MechaKalyani and Chitrambhari respectively. Such methods of allocating janaka melas , though logical, are merely mechanical and will not find support.

It will be useful at this stage to ponder awhile about the rules observed in fixing Janaka raga for Janya ragas. All janya ragas must either be upanga or bhashanga.

The following considerations are taken into account in fixing their janaka ragas :

In the case of the upanga ragas of the audava - sampurna , sampurna- audava , shadava – sampurna and sampurna – vakra varieties , the janaka ragas are easily determined , since all the saptaswaras are represented in either the arohana or avarohana. It is also easy to determine the janaka ragas for the upanga ragas of the shadava – shadava , shadava – audava , audava – shadava and audava – audava types , if in each case , the saptaswaras are found represented in the arohana and avarohana taken together. It is likewise easy to fix the janaka ragas for the Panchama – varjya shadava – shadava , shadava – audava , audava – shadava and audava – audava , ragas of the upanga type , provided the notes rishabha , gandhara , madhyama , dhaivata and nishada are represented in the arohana nad avarohana taken together. The difficulty arise only in the case of those upanga ragas wherein one or two notes are completely eliminated in both the arohana and avarohana.

Taking Mohana , for instance , it might be argued that it can be taken as a derivative of the Dheera Shankarabharana , Vachaspathi and Mecha Kalyani melas also , taking into consideration its swarasthanas. Likewise Sarasangi , Lathangi and Mecha Kalyani might be cited as the other possible janaka melas for Hamsadhwani ; and Nattabhairavi , Charukeshi and Harikambhoji as the other possible janaka melas for Madhyamavathi.

The author of the Sangeetha Kaumudi tried to find a solution for this anormaly by enunciating a new rule – that , all such cases the raga should be allocated to the earliest possible mela in the scheme of 72. This theory naturally ignored all the relevant and important considerations that have weighed with music scholars in the past in fixing the janaka melas for janya ragas considerations like :

- Suggested affinities to particular melas ( eg. Malahari ).

- The subtle srutis figuring the janya raga ( eg. Kambhoji ) and

- The history behind the development of the janya ragas ;

were deemed really important in determining the janaka melas. The theory referred to the above takes into consideration only the swarasthanas of a raga. The author of this theory was naturally led to place Kuntalavarali under Vanaspathi , Malahari undr Gayakapriya , Nagaswaravali undr Chakravakam , Madhyamavati under Nattabhairivi and so on.

As a corollary to the theory suggested by the author of the Sangita Kaumudi , we may enunciate the theory that all janya ragas should be allocates to the latest possible melas in the scheme of 72. Mohana and Hamsadwani under this theory will rank as janyas of MechaKalyani and Chitrambhari respectively. Such methods of allocating janaka melas , though logical, are merely mechanical and will not find support.

Kriyanga Ragas

The term kriyanga raga does not denote any particular type of raga in modern music. Different scholars in the past held different views regarding the exact connotation of this term. The Sandita Darpana (1625 A.D. ) of Damodara Misra mentions that kriyanga ragas were those infused enthusiasm in us. Others held that they were the same as vakra ragas ; and some others thought that they were sankirna ragas. Yet others thought that they were ragas whose names had the suffix- kriya; thus Devakriya, Gundakriya, Ramakriya, Sindhuramakriya , Gamakakriya, etc. A few held the view that they were those which took foreign notes.

The term kriyanga raga has now no significance and has rightly become obsolete. The various interpretations given to this term in the past are now covered by other technical terms or concepts.

The term kriyanga raga does not denote any particular type of raga in modern music. Different scholars in the past held different views regarding the exact connotation of this term. The Sandita Darpana (1625 A.D. ) of Damodara Misra mentions that kriyanga ragas were those infused enthusiasm in us. Others held that they were the same as vakra ragas ; and some others thought that they were sankirna ragas. Yet others thought that they were ragas whose names had the suffix- kriya; thus Devakriya, Gundakriya, Ramakriya, Sindhuramakriya , Gamakakriya, etc. A few held the view that they were those which took foreign notes.

The term kriyanga raga has now no significance and has rightly become obsolete. The various interpretations given to this term in the past are now covered by other technical terms or concepts.

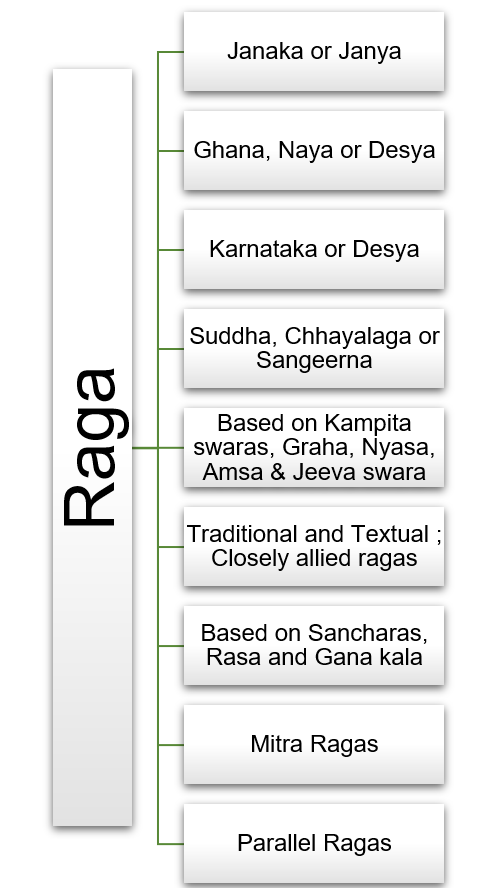

Other general classifications

In addition to the janaka-janya system, ragas in general have been classified into:

Ghana, Naya and Desya

Ghana : One which is very majestic in nature and vibrant with brisk swara passages. A Ghana raga is a raga whose characteristic individuality is brought about more easily by madhyamakala or tana (ghanam) in it. In such ragas, the notes may be played in a plain and unadorned manner without detriment to raga bhava.

Examples: The traditional five ghana ragas ( ghana panchaka): Nata, Goula, Arabji, Sriraga and Varali.

Krdaram, Narayanagaula, Ritigaula, Saranganata and Bauli are another series of five ghana ragas and are reffered to as the Dvitiya ghana panchakam.

Naya : One which is very elaborative and heavy in classicism. In a naya or rakti raga, the characteristic individuality is brought about both by alapana in slow tempo and tana.

Examples: Todi, Bhairavi, Kambhoji, Sankarabharana and Kalyani.

Desya : One which is very pleasant, soothing and light to perform. In desya raga, the characteristic individuality is easily brought by alapana.

Examples: Knanda, Hindusthan Kafi, Jhinjhoti and Hindusthan Behag.

Sometimes the term ghana raga is loosely used in the sense of a raga affording wide scope for alapana. Ragas usually resorted to for Pallavi exposition in concerts are in a this sense, referred to as ghana raga.

Some scholars regard ghana ragas as those which have a grand and majestic effect ; naya or rakti ragas as those which has a soothing effect and desya ragas as those which have combine in themselves the effects of both these types of ragas. This concept has its parallel in the Purusha (male), Stri (female) and Putra (children) ragas.

It may be of interest to note that in the kachcheri paddhati (concert program), the sequence of ghana-naya-desya is generally adhered to. This sequence is based on an aesthetic and logical principal. Vidhvans in the past began their concerts with ghana ragas, followed them up with the rendering of compositions and pallavis in naya or rakti ragas and concluded with delightful alapanas of desya ragas. Tana varanas have now usurped the place of the ghana ragas.

Karnataka and Desya

Karnataka : Ones which originated and developed indigenously to South India, like Bhairavi, Anandha Bhairavi, Kedaragaula, Nilambari and Sankarabharanam.

Desya: Ones which are adopted from Hindustani system or any other Music system and became popular in the South. Example: Pharaz, Jhinjhoti, Desh, Mand, Hindusthan Behag and Hamin Kalyani.

This is a geographical classification and has acquired significance since the time the bifurcation into the two systems of music, Karnatic and Hindusthani took place.

In addition to the janaka-janya system, ragas in general have been classified into:

Ghana, Naya and Desya

Ghana : One which is very majestic in nature and vibrant with brisk swara passages. A Ghana raga is a raga whose characteristic individuality is brought about more easily by madhyamakala or tana (ghanam) in it. In such ragas, the notes may be played in a plain and unadorned manner without detriment to raga bhava.

Examples: The traditional five ghana ragas ( ghana panchaka): Nata, Goula, Arabji, Sriraga and Varali.

Krdaram, Narayanagaula, Ritigaula, Saranganata and Bauli are another series of five ghana ragas and are reffered to as the Dvitiya ghana panchakam.

Naya : One which is very elaborative and heavy in classicism. In a naya or rakti raga, the characteristic individuality is brought about both by alapana in slow tempo and tana.

Examples: Todi, Bhairavi, Kambhoji, Sankarabharana and Kalyani.

Desya : One which is very pleasant, soothing and light to perform. In desya raga, the characteristic individuality is easily brought by alapana.

Examples: Knanda, Hindusthan Kafi, Jhinjhoti and Hindusthan Behag.

Sometimes the term ghana raga is loosely used in the sense of a raga affording wide scope for alapana. Ragas usually resorted to for Pallavi exposition in concerts are in a this sense, referred to as ghana raga.

Some scholars regard ghana ragas as those which have a grand and majestic effect ; naya or rakti ragas as those which has a soothing effect and desya ragas as those which have combine in themselves the effects of both these types of ragas. This concept has its parallel in the Purusha (male), Stri (female) and Putra (children) ragas.

It may be of interest to note that in the kachcheri paddhati (concert program), the sequence of ghana-naya-desya is generally adhered to. This sequence is based on an aesthetic and logical principal. Vidhvans in the past began their concerts with ghana ragas, followed them up with the rendering of compositions and pallavis in naya or rakti ragas and concluded with delightful alapanas of desya ragas. Tana varanas have now usurped the place of the ghana ragas.

Karnataka and Desya

Karnataka : Ones which originated and developed indigenously to South India, like Bhairavi, Anandha Bhairavi, Kedaragaula, Nilambari and Sankarabharanam.

Desya: Ones which are adopted from Hindustani system or any other Music system and became popular in the South. Example: Pharaz, Jhinjhoti, Desh, Mand, Hindusthan Behag and Hamin Kalyani.

This is a geographical classification and has acquired significance since the time the bifurcation into the two systems of music, Karnatic and Hindusthani took place.

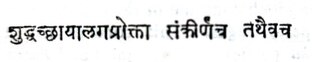

Sudha, Chayalaga and Sankeerna

This is an old system of classification and was propounded before the janaka-janya system came into vogue.

This is an old system of classification and was propounded before the janaka-janya system came into vogue.

This sloka is quoted in the Sangitha Darpana of Damodara Misra. This classification is based on the nadatma rupa of ragas.

Suddha ragas : One which does not have any similarity with any other melody. They were pure ragas and they conformed to prescribed rules. They included within their compass the modern melakartha ragas and the janya ragas of the upanga type.

Example: Mayamalavagowla, Madhyamavati, Sriranjini, Mohana, Kalyani.

Chayalaga : One which has traces of some other raga in its progression. A chayalaga or salaka or salaga raga was a raga which combined in itself the lakshana of another raga by taking a foreign note or by possessing common sancharas. That is, the chaya, trace or shade of another raga or the colour of another raga was found in a salaga raga in a remote manner.

Example: Saurashtra, Saranga.

A salaga raga need not necessarily be a bhashanga raga. Bilahari may be cited as an example of a bhashanga raga of the non-chayalaga type and Surashtra as an example of a bhashanga raga of the chayalaga type.

Sankeerna : One which is very complicated as it is linked with several ragas. A sankirna, sankrama or misra raga was a mixed raga. Traces of more than one raga were discernible in such ragas either on account of the presence of foreign notes or sancharas suggestive of other ragas. Sankeerna ragas are extreme types of chayalaga ragas. The chayas of the foreign ragas are very pronounced in them. Nevertheless, sankeerna ragas have their own melodic individuality.

Example: Ahiri, Ghanta, Manji, Jujavanti.

In Jujavanti (also called Dvijavanti), one can see in its sancharas, traces of Kedaragowla, Sahana and Yadukulakambhoji. By their very nature, sankeerna ragas do not give scope for an elaborate alapana. There are many folk melodies in misra ragas.

Suddha ragas : One which does not have any similarity with any other melody. They were pure ragas and they conformed to prescribed rules. They included within their compass the modern melakartha ragas and the janya ragas of the upanga type.

Example: Mayamalavagowla, Madhyamavati, Sriranjini, Mohana, Kalyani.

Chayalaga : One which has traces of some other raga in its progression. A chayalaga or salaka or salaga raga was a raga which combined in itself the lakshana of another raga by taking a foreign note or by possessing common sancharas. That is, the chaya, trace or shade of another raga or the colour of another raga was found in a salaga raga in a remote manner.

Example: Saurashtra, Saranga.

A salaga raga need not necessarily be a bhashanga raga. Bilahari may be cited as an example of a bhashanga raga of the non-chayalaga type and Surashtra as an example of a bhashanga raga of the chayalaga type.

Sankeerna : One which is very complicated as it is linked with several ragas. A sankirna, sankrama or misra raga was a mixed raga. Traces of more than one raga were discernible in such ragas either on account of the presence of foreign notes or sancharas suggestive of other ragas. Sankeerna ragas are extreme types of chayalaga ragas. The chayas of the foreign ragas are very pronounced in them. Nevertheless, sankeerna ragas have their own melodic individuality.

Example: Ahiri, Ghanta, Manji, Jujavanti.

In Jujavanti (also called Dvijavanti), one can see in its sancharas, traces of Kedaragowla, Sahana and Yadukulakambhoji. By their very nature, sankeerna ragas do not give scope for an elaborate alapana. There are many folk melodies in misra ragas.

Svasthana visada raga : Gamaka sruti visada raga

There are ragas like hamsadhvani, whosw individualities are revealed even when their notes are sounded in a plain manner. Such ragas are called svasthana visada ragas. On the other hand, there are ragas like Ahiri and Kanada whose notes when sounded in a plain manner will not reveal the raga. The notes have to be sounded with the subtle srutis and delicate graces. Such ragas are styled gamaka- sruti visada ragas.

There are ragas like hamsadhvani, whosw individualities are revealed even when their notes are sounded in a plain manner. Such ragas are called svasthana visada ragas. On the other hand, there are ragas like Ahiri and Kanada whose notes when sounded in a plain manner will not reveal the raga. The notes have to be sounded with the subtle srutis and delicate graces. Such ragas are styled gamaka- sruti visada ragas.

Classification based on Kampita swaras

- Sarva swara gamaka varika ragas or muktanga ragas or sampurna kampita ragas are ragas wherein all the notes figuring in them are subject gamaka. Eg: Todi, Mohana and Kalyani. Shadja swara being tonic note Is not subject to kampita. If shadja is shaken, it may lead to vivaditva. However, in some rare prayogas, one may notice the illusion of kampita in shadja swara. Panchama swara is in some rare cases rendered with kampita.

- Ardha kampita ragas are those wherein some of the notes figuring in the raga are subject to kampita. Eg: Kuntalavarali.

- Kampa vihina ragas are those wherein the notes may be played substantially pure i.e., without shake and at the same time without detriment to raga bhava. Eg: Kadanakutuhalam and Sindhuramakriya (Devadi deva Sadasiva).

Classification based on Nyasa Swaras

According to the nyasa swaras admissible, ragas may be classified into :

Shaja is a common Nyasa swara for all ragas. A raga may have more than one nyasa swara. In a raga admitting of plural nyasa swaras, the nyasa swaras may admit of the classification, purna and alpa. A purna nyasa swara is a note on which one can sustain for a length of time. Eg: Panchama in Bhairavi raga. An alpa nyasa swara is one on which one can just conclude without stressing or pausing, as the note Chatursruti dhaivatha in the phrases S n d, R S n d ( cap letters are tara stayi) in Bhairavi and Mukhari ragas. Another example is pa in the phrase S n d n p in Natakuranji raga. Purna nyasa swaras are called major nyasa swaras and alpa nyasa swaras are called minor nyasa swaras. Hamsadhwani and Mohana are examples of Sarva swara nyasa ragas.

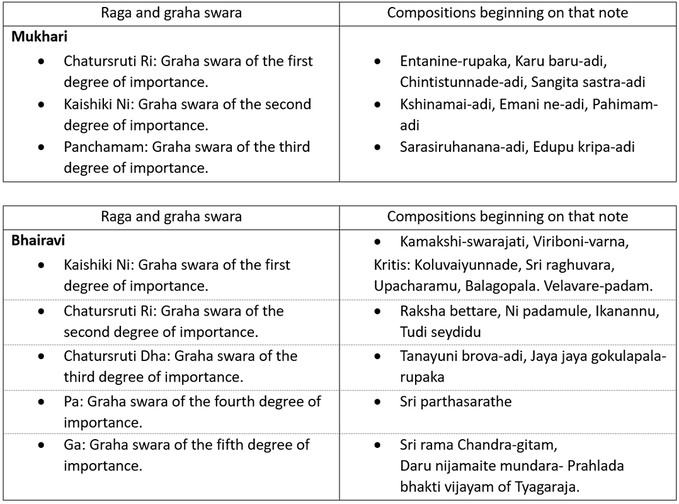

Classification based on Graha swaras , Jiva swaras and Amsa swaras.

The notes on which melodies can commence in a raga called Graha swaras are taken into account here. For example, Gandhara is a graha swara in Mohana raga; and nishada is a graha swara in Bhairavi raga. Some ragas admit of more than one graha swara.

In a raga with plural graha swaras, the graha swaras will be found to be of varying degrees of status. According to degree of importance of the graha swaras, they may be analysed and classified into those belonging to:

The notes on which classical compositions begin, furnish the necessary clues. The largest number of compositions will be found to begin on the graha swara of the first degree of importance. A fairly good number of compositions will be found to begin on the note of the second degree of importance. A few compositions will be found to begin on the graha swara of the third of importance and so on.

According to the nyasa swaras admissible, ragas may be classified into :

- Rishabha nyasa raga: Kedaragowla, Arabhi

- Gandhara nyasa raga: Sankarabharana

- Madhyama nyasa raga: Kuntalavarali, Khamas

- Panchama nyasa raga: Shanmukhapriya

- Dhaivatha nyasa raga: Saveri, Athana

- Nishada nyasa raga: Hamsadhwani

Shaja is a common Nyasa swara for all ragas. A raga may have more than one nyasa swara. In a raga admitting of plural nyasa swaras, the nyasa swaras may admit of the classification, purna and alpa. A purna nyasa swara is a note on which one can sustain for a length of time. Eg: Panchama in Bhairavi raga. An alpa nyasa swara is one on which one can just conclude without stressing or pausing, as the note Chatursruti dhaivatha in the phrases S n d, R S n d ( cap letters are tara stayi) in Bhairavi and Mukhari ragas. Another example is pa in the phrase S n d n p in Natakuranji raga. Purna nyasa swaras are called major nyasa swaras and alpa nyasa swaras are called minor nyasa swaras. Hamsadhwani and Mohana are examples of Sarva swara nyasa ragas.

Classification based on Graha swaras , Jiva swaras and Amsa swaras.

The notes on which melodies can commence in a raga called Graha swaras are taken into account here. For example, Gandhara is a graha swara in Mohana raga; and nishada is a graha swara in Bhairavi raga. Some ragas admit of more than one graha swara.

In a raga with plural graha swaras, the graha swaras will be found to be of varying degrees of status. According to degree of importance of the graha swaras, they may be analysed and classified into those belonging to:

- The first degree of importance,

- Second degree of importance,

- Third degree of importance and so on.

The notes on which classical compositions begin, furnish the necessary clues. The largest number of compositions will be found to begin on the graha swara of the first degree of importance. A fairly good number of compositions will be found to begin on the note of the second degree of importance. A few compositions will be found to begin on the graha swara of the third of importance and so on.

Many ragas admit of plural jiva swaras and amsa swaras.

Classification based on Sancharas

Ragas may be classified into:

- Those which admit of only krama sancharas or phrases in conformity with the contour of the arohana and avarohana

- Those which in addition to krama sancharas admit of visesha sancharas or phrases not in accordance with the pattern, contour or structure of the arohana and avarohana.

Mohana is an example of the former class and Dhanyasi that is of the latter class. The phrase p n S d p (cap letters are tara stayi) occurs in Dhanyasi as a visesha sanchara.

Normally, compositions can commence only with krama sancharas. But ragas like Sankarabharana and Kambhoji are exceptions. Varnas in Kambhoji raga commence with the visesha sanchara

m g s, n. p. d. s (letter with dot after them are mandra stayi).

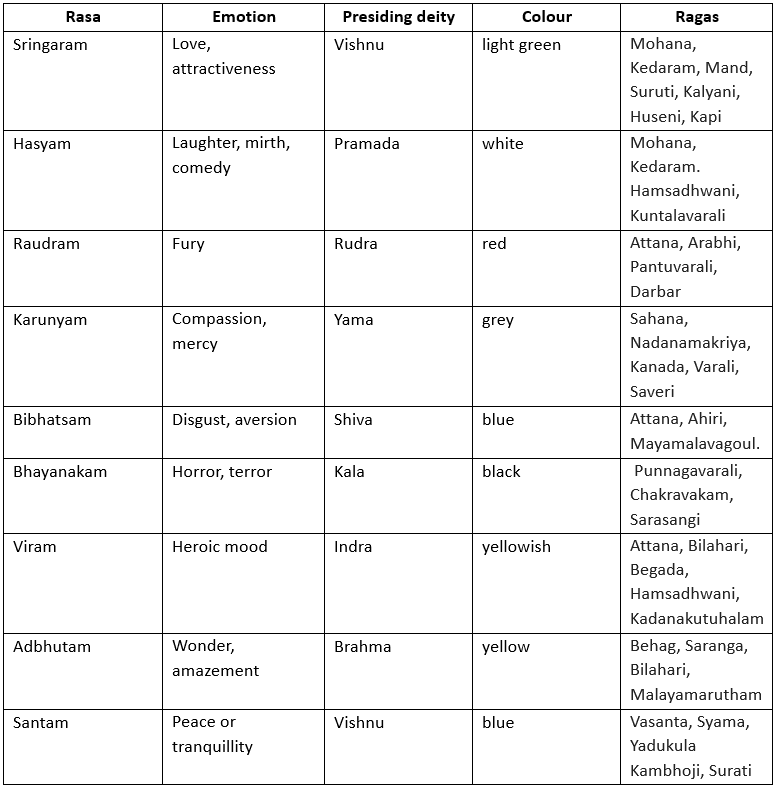

Classification based on Rasa

Ragas can be classified according to their rasas i.e., the feelings they arouse in us.

Bharata Muni enunciated the eight Rasas in the Natyasastra, an ancient work of dramatic theory. Each rasa, according to Natyasastra, has a presiding deity and a specific colour. The aura of a frightened person is black, and the aura of an angry person is red. Bharata Muni established the following.

The nineth rasa was added by later authors. This addition had to undergo a good deal of struggle between the sixth and the tenth centuries, before it could be accepted by the majority of the Alankarikas, and the expression Navarasa (the nine rasas), could come into vogue.

Punnagavarali and Nadanamakriya are instances of ragas which arouse the feeling of pathos (pity or sadness). Athana, Sama and Sahana are respectively examples of raudra, santa, and karuna rasas. Khamas is a good example of a raga for sringara rasa(love). Some ragas are capable of arousing two or more feelings. Even in such cases it is possible to say which is the primary or the dominant rasa in the raga and which is the secondary rasa and so on.

Punnagavarali and Nadanamakriya are instances of ragas which arouse the feeling of pathos (pity or sadness). Athana, Sama and Sahana are respectively examples of raudra, santa, and karuna rasas. Khamas is a good example of a raga for sringara rasa(love). Some ragas are capable of arousing two or more feelings. Even in such cases it is possible to say which is the primary or the dominant rasa in the raga and which is the secondary rasa and so on.

Classification based on gana kala or the time of singing

Ragas in general may be classified according to the time of the day or night or seasons during which they should be sung. There are some ragas which may be sung at all times. These are called sarvakalika ragas.

Eg: Chakravaka, Bhairavi, Kambhoji and Arabhi.

Ragas in general may be classified according to the time of the day or night or seasons during which they should be sung. There are some ragas which may be sung at all times. These are called sarvakalika ragas.

Eg: Chakravaka, Bhairavi, Kambhoji and Arabhi.

The pans of the Tevaram are also classified into :

(1)Pagal pan - to be sung during day.

(2)Iravup pan - to be sung during night

(3)Poduppan - which can sung at all times.

The time theory of ragas is based on the principal that ragas sound best when sung or performed during the allotted time. The rule is however not of a mandatory nature but of an advisory character. The fact that when a king asks for a raga, a vidvan can sing it, irrespective of the time or season during which it should be sung, shows that the rule relating to the time for singing a ragas is not an inviolable one.

Ragamalika compositions are another instance in point. They necessarily contain in them ragas with varying gana kala. Once commenced, the entire composition has however to be sung continuously.

The last section of a ragamalika is always in an auspicious raga, just to neutralize the supposed evil effects that might result by singing the ragas figuring in the ragamalika out of their allotted time.

It is the practice however to choose for detailed alapana in a concert, only a raga whosegana kala synchronises with the time of the concert. For instance, when vidvans are requested to give concerts in mornings, they make a detailed alapana of Dhanyasi and follow it up with a Pallavi in that raga. In the case of sarvakalika ragas, this problem does not arise.

Closely allied ragas

These ragas are derivative of the same mela and yet differ from each other from the following points of view:

(1) Ranjaka Prayogas or Pakads

Eg: Bhairavi and Manji. Manji has the characteristic prayoga d p G , p G R s

(2) Mouthing and intonation of the Arohana and Avarohana.

Eg: Sama and Arabhi

(3) Tempo in rendering.

Eg: Arabhi and Devagandhari. These two are janyas of the same mela and take the same Arohana and Avarohana, but still differ from each other. Chauka kala Prayogas are the characteristic feature of Devagandhari whereas madhyama kala prayogas are the essential feature of Arabhi.

(4) Difference in the renderings of gamakas: Ghanta and Punnagavarali

(5) Tessitura being confined to a part of the middle octave and the higher octave.

Eg: Bilahari and Desakshi ragas. Phrases in Bilahari raga can embrace all the 3 octaves, but phrases in Desakshi raga are confined to the middle and higher octaves.

(6)Delicate srutis. Eg; Darbar and Nayaki

(7) Slight change in the Arohana and Avarohana

Eg: Kedaragaula and Narayanagoula ragas. These are Janyas of the 28th mela and are upanga ragas. Still they differ from each other on account of Narayanagowla taking an Ubhayavakra Arohana and Avarohana and Kedaragowla taking a Krama Audava- sampurna Arohana and Avarohana.

Traditional ragas and Textual ragas

Traditional ragas come through long sampradaya and are many centuries old. Kedaragaula and Nata are examples. Textual ragas are those mentioned in the Lakshana Grandhas written during the last few centuries. Eg; Valaji.

Mitra ragas

Ragas whose names possess common ending are called mitra ragas. During the medieval period, when few ragas existed, raga names of that period with common endings had some relationship. With the emergence of a number of ragas later on with similar endings in their names, this original relationship has practically lost its significance. At present, excepting for this common terminology, there is nothing else in common between these ragas.

Examples:

Ritigaula, Narayanagaula, Kedaragaula, Chhayagaula, Malavagaula and Kannadagaula

Natakapriya, Kokilapriya, Bhavapriya, Ramapriya, Shanmukhapriya, Rishabhapriya and Rasikapriya

Gundakriya, Sindhuramakriya, Nadanamakriya, Devakriya and Gamakakriya

Harikambhoji, Yadukulakambhoji, Chenchukambhoji, Gummakambhoji, Hamsakambhoji, Purnakambhoji, Kuntalakambhoji, Sudhakambhoji and Sajjakambhoji

Hindolavasanta, Gopikavasanta and Mallikavasanta

Garudadhvani, Nagadhvani, Hamsadhvani, Kokilashvani, Pikadhvani, Jhankaradhvani and Mayuradhvani

Gambhiranata, Ahirinata, Saranganata and Chhayanata

Sarasvatimanohari, Devamanohari, Isamanohari, Ramamanohari, Jayamanohari, Kamalamanohari and Madhavamanohari

Punnagavarali, Kokilavarali, Vasantavarali, Pratapavarali, Sokavarali, Pantuvarali and Kuntalavarali

Jayantasri, Malavasri and Viyasri

Gaulipantu and Mukharipantu

The above examples have a terminal symmetry. In the same manner, we can pick out ragas whose names have initial symmetry.

-Kokilapriya, Kokilavarali, Kokilabhashini and Kokiladhvani

Punnagavarali and Punnaga todi

After the advent of the janaka-janya system, the classification into mitra ragas has ceased to be of any importance.

Ragas which can aptly succed one another in a ragamalika are also termed mitra ragas. Therefore a raga which may be a mitra raga (friend) for a particular raga may become a satru raga (enemy) for another.

Ragas whose names possess common ending are called mitra ragas. During the medieval period, when few ragas existed, raga names of that period with common endings had some relationship. With the emergence of a number of ragas later on with similar endings in their names, this original relationship has practically lost its significance. At present, excepting for this common terminology, there is nothing else in common between these ragas.

Examples:

Ritigaula, Narayanagaula, Kedaragaula, Chhayagaula, Malavagaula and Kannadagaula

Natakapriya, Kokilapriya, Bhavapriya, Ramapriya, Shanmukhapriya, Rishabhapriya and Rasikapriya

Gundakriya, Sindhuramakriya, Nadanamakriya, Devakriya and Gamakakriya

Harikambhoji, Yadukulakambhoji, Chenchukambhoji, Gummakambhoji, Hamsakambhoji, Purnakambhoji, Kuntalakambhoji, Sudhakambhoji and Sajjakambhoji

Hindolavasanta, Gopikavasanta and Mallikavasanta

Garudadhvani, Nagadhvani, Hamsadhvani, Kokilashvani, Pikadhvani, Jhankaradhvani and Mayuradhvani

Gambhiranata, Ahirinata, Saranganata and Chhayanata

Sarasvatimanohari, Devamanohari, Isamanohari, Ramamanohari, Jayamanohari, Kamalamanohari and Madhavamanohari

Punnagavarali, Kokilavarali, Vasantavarali, Pratapavarali, Sokavarali, Pantuvarali and Kuntalavarali

Jayantasri, Malavasri and Viyasri

Gaulipantu and Mukharipantu

The above examples have a terminal symmetry. In the same manner, we can pick out ragas whose names have initial symmetry.

-Kokilapriya, Kokilavarali, Kokilabhashini and Kokiladhvani

Punnagavarali and Punnaga todi

After the advent of the janaka-janya system, the classification into mitra ragas has ceased to be of any importance.

Ragas which can aptly succed one another in a ragamalika are also termed mitra ragas. Therefore a raga which may be a mitra raga (friend) for a particular raga may become a satru raga (enemy) for another.

Common ragas or Parallel ragas

Harmonic minor scale of Western music corresponds to Kiravani of Carnatic music.

There are also ragas common to both Carnatic and Hindusthani systems of music like Mohana and Bhupali; Suddhasaveri and Durga; Mayamalavagaula and Bhairav; Hindolam and Malkaus.

Senjurutti of Carnatic music and Jhinjhoti of Hindusthani music are nearly allied ragas. Both are derivatives of the same mela, Harikambhoji of Carnatic music or Khamaj That of Hindusthani music. But Senjurutti is an upanga raga and does not take sadharana Gandhara as a foreign note; while Jhinjhoti takes the sadharana Gandhara as a foreign note.

There are compositions of both thses ragas. The Svarajati, Manayaka and the songs: Kamala nayana Vasudeva ( Bhadrachala Ramadas), Rama Rama (tyagaraja), Saranu Saranu (Anayya) and Inta tamasa melane (Cheyyur Chengalvaraya Sastri) are in Senjuruti raga. The Javali, Sakhi prana is in Jhinjhoti raga.

Harmonic minor scale of Western music corresponds to Kiravani of Carnatic music.

There are also ragas common to both Carnatic and Hindusthani systems of music like Mohana and Bhupali; Suddhasaveri and Durga; Mayamalavagaula and Bhairav; Hindolam and Malkaus.

Senjurutti of Carnatic music and Jhinjhoti of Hindusthani music are nearly allied ragas. Both are derivatives of the same mela, Harikambhoji of Carnatic music or Khamaj That of Hindusthani music. But Senjurutti is an upanga raga and does not take sadharana Gandhara as a foreign note; while Jhinjhoti takes the sadharana Gandhara as a foreign note.

There are compositions of both thses ragas. The Svarajati, Manayaka and the songs: Kamala nayana Vasudeva ( Bhadrachala Ramadas), Rama Rama (tyagaraja), Saranu Saranu (Anayya) and Inta tamasa melane (Cheyyur Chengalvaraya Sastri) are in Senjuruti raga. The Javali, Sakhi prana is in Jhinjhoti raga.

Janya raga classifications

Raga Classification in General

The classifications pointed out in the above picture are not mutually exclusive. For example , a janaka raga like Mayamalavagaula is a suddha raga and also a rakti raga; a janya raga like Hamir Kalyani is chhayalaga raga and also a desya raga and so on.

In some ubhaya vakra ragas, the Viloma (reverse) versions of the arohana and avarohana will be found to agree with the Krama versions of the arohana and avarohana.

Mechakangi (53) – s r g m p d p n S _ S n p d p m g r s

Yamunakalyani (65) – s r g p m p d S _ S d p m p g r s

In some ubhaya vakra ragas, the Viloma (reverse) versions of the arohana and avarohana will be found to agree with the Krama versions of the arohana and avarohana.

Mechakangi (53) – s r g m p d p n S _ S n p d p m g r s

Yamunakalyani (65) – s r g p m p d S _ S d p m p g r s

|

Gmail : vaikampadmakrishnan@gmail.com

Mobile & WhatsApp : +91 9446535161 Skype : vaikampadmakrishnan Instagram : Vaikam Padma Krishnan |